A contactor is an electrical device, a specific type of relay. It is used to switch an electrical circuit ON or OFF. It is very useful for high-power applications for its capacity of to control circuits of high voltage or current levels.

One of the common application examples is in electrical motors. Here, they can perfectly control the starting and stopping. Contactors are essential components in many industrial control systems.

This is because they are designed to handle heavy loads and provide safety features. The present article addresses what contactors are, how do they work, where are they used, their pros and cons, and to do the maintenance and troubleshooting.

The Contractors

Different from general-purpose relays, contactors are built with features for safety and durability. These characteristics include suppression of arc systems and the ability to be mounted on standard rails (DIN rails).

In order to select a contactor, it depends on the load consumption of current and voltage.

Key Components of Contactors

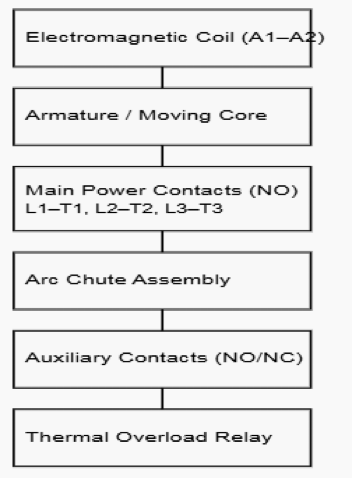

A contactor has several key parts, which work together to operate the switch. The main components are the coil (electromagnet), the contacts, and the enclosure (frame):

- Coil: An electromagnet used to create a magnetic field when energized.

- Contacts: These are the actual electrical switches that are physically moved by the coil due to its magnetic field.

- Enclosure (frame): This provides a case for the internal components

The following figure illustrates a schematic for the internal components of a contactor.

Working Principle

The coil is the most important part of the operation. It is used to generate a magnetic field when energized. This magnetic field is what makes the contactor switch the circuit.

There must be a control voltage to activate the coil. This control voltage is usually much lower than the main circuit voltage. For instance, a contactor might control a 240 V motor, while its coil might only have 24 volts to activate.

So, just to emphasize, the coil is a very important part, and there must be a control voltage for it to operate.

When power is applied to the coil, it creates an electromagnetic force. This force pulls a movable armature toward a stationary core.

It is important that the control voltage to be exactly the same as coil-specified rating. When an incorrect voltage is applied, this could lead to catastrophic outcomes to the coil.

In addition, the mechanical movement is physically operates the contacts. While, the main role of the contacts is to handle applied power. These are the ones that deals with the actual switching mechanism.

They can be found in two main sub-parts: fixed and movable. Once the coil is energized, the movable ones touch the fixed ones. This makes the power circuit complete. By de-energizing the coil, springs pull the movable contacts away.

Then the power circuit can no longer stay complete. Special metal alloys are selected for the contacts. These metals designed to withstand arc damage and mechanical wear. This harsh and sturdy design is essential for long service life. The choice of material guarantees a dependable connection every time.

The enclosure (frame) works as the back-bone of structural housing. It keeps all components securely in place. It also shields the device from external conditions. The enclosure is typically built from insulating materials.

This helps protect operators from electric shock. It also reduces the entry of dust or moisture. The frame is designed for easy installation. It is commonly mounted on a standard DIN rail in industrial panels. The enclosure frequently contains the arc chutes as well.

Consider an image below; it shows the assembled contactors with mounting points.

Arc suppression is an essential protective feature. High voltage and current create an electrical arc as the contacts open. This arc resembles a tiny lightning bolt. It can harm the contacts and pose a fire risk.

Contactors incorporate arc chutes to control this. Arc chutes are shaped chambers to cool and quench the arc rapidly. They guide the arc away from the contact surfaces.

This approach greatly increases the lifespan of the contacts. Magnetic blowouts can also work together with the arc chutes.

Auxiliary Contacts

Contactors may include auxiliary contacts. These are additional sets of contacts. They operate independently from the main power contacts. Auxiliary contacts function in the control circuit. They often supply status signals to the control system.

For instance, they may activate a lamp to show that the main circuit is energized. They can be normally open (NO) or normally closed (NC). They move in sync with the main contacts. Their electrical ratings are much lower than those of the main contacts.

Overload protection

Overload protection is essential when using a contactor. A motor may pull excessive current if it is obstructed. This “overload” can harm the motor and wiring. Thermal overload relays are commonly paired with a contactor.

They track the motor’s current. If the current remains too high for too long, the relay trips. The relay interrupts the control circuit feeding the coil. This causes the contactor to drop out and stop the motor. The overload relay is a separate unit mounted alongside the contactor.

Similarities and Differences with Relays

A relay resembles a contactor but differs in capability. Relays are mainly for low-power duties. They support smaller voltages and currents. Contactors are engineered for heavy electrical loads.

Contactors typically include enhanced safety measures like arc suppression. Relays are used widely in electronic systems. Contactors dominate in industrial motor applications.

A relay may come with many contact arrangements. Contactors generally feature main contacts that are normally open.

Main Applications

This section covers the primary uses of contactors.

Motor starting

Motor starting is one of their main uses. Contactors are key components in motor starter circuits. A basic starter consists of a contactor, plus an overload relay. Pressing a “start” button energizes the coil.

Pressing a “stop” button deactivates the coil. Auxiliary-contact interlocks maintain safe starting and stopping sequences. This simple setup forms the foundation of many industrial control systems.

It allows centralized or remote operation of large motors. The upcoming figure indicates a very basic motor starter-schematic.

Lighting control

Lighting control is another major use. Large commercial or industrial lighting loads consume significant power. Contactors switch these large lighting circuits. A small wall switch can control the contactor coil.

The contactor then controls the main lighting supply for large groups of fixtures. This is more effective than using many small relays. It consolidates lighting control. This creates a strong and dependable solution for large facilities.

Capacitor switching

Capacitor switching requires specialized contactors. Power factor correction systems employ capacitor banks. Switching capacitors draws high inrush currents. Standard contactors would be damaged by these surges.

Dedicated capacitor contactors include pre-charge resistors. These resistors limit the initial surge current. The main contacts close once the surge is contained. This arrangement increases the service life of both the contactor and the capacitors.

Other Types of Contactors

Vacuum contactors

Vacuum contactors serve specialized environments. Their contacts sit inside a vacuum chamber. The vacuum eliminates arcing completely. With no air to ionize, arc formation is prevented. This makes them extremely durable.

They work well in very high-voltage applications. Mining operations and heavy industries frequently use them. Their sealed design is also safe where hazards exist. They require less upkeep compared to open-air designs.

Solid-State Contactors

Solid-state contactors are available but operate differently. They use semiconductor devices rather than mechanical contacts. With no moving parts, they avoid contact wear and arcing. They switch extremely quickly.

They are ideal for applications with repeated switching, such as heating control. However, they generate heat and need proper heat sinking. They may also cost more than magnetic contactors.

Maintenance and Troubleshooting

Maintenance is essential for contactors. Regular checks are advisable. Inspect for worn or pitted contacts. Watch for loose terminals. Listen for unusual sounds during use. A chattering noise may suggest low coil voltage.

Replace damaged contacts before they cause failure. Good maintenance ensures safety. It also extends the life of the system. Always follow the manufacturer’s instructions.

On the other hand, troubleshooting typical problems is straightforward. If a contactor vibrates loudly, the coil could be faulty. A mechanical obstruction may stop the armature from seating fully. If the device does not pull in, check the control voltage.

The coil may be burnt. If the load does not receive power, the main contacts may be defective. A multimeter is useful for testing. Always follow safety rules when inspecting equipment. Shut off all power before starting.

Key Takeaways: What is a Contactor?

This article explored what contactors are, how do they work and where are they used It also studied their pros and cons, and how to do the maintenance and troubleshooting.

So, awe have seen that contactor is a durable electrical switching device. It is built for high-power operation.

It uses a low-power input to manage large electrical loads. Its main components include the coil, contacts, and arc chutes. It is essential in industry.

It safely controls motors, lighting, and other large electrical systems. Knowing how it works helps in building safe designs. Choosing the correct contactor is important for dependable operation.

FAQ: What is a Contactor?

What is a contactor?

A contactor is an electromechanical switch (like a heavy-duty relay). It is designed to open or close high-power electrical circuits such as for lighting, motors, heating or other heavy loads.

How does a contactor work?

When a coil is energized, it creates a magnetic field. This pulls a movable core (armature) closing the main contacts and allowing power to flow.

On the contrary, when the coil is de-energized, a spring releases the armature. So, the contacts open to interrupt the load circuit.

What makes a contactor different from a regular relay?

Contactors are for handling much higher currents and voltages than typical relays. They are designed for power-switching, while relays often deal with low-power control circuits.

Where are contactors commonly used?

Motor starter circuit, large lighting banks and heating systems. Also, capacitor banks, and other high-power loads in industrial, commercial or heavy-duty environments.

What are the basic parts of a contactor?

The main parts are: a coil (electromagnet), main power contacts (and sometimes auxiliary contacts), armature (movable core), an insulating housing (enclosure), and springs or return mechanism.

Is a contactor safe for switching large loads remotely?

Yes, because the control circuit (coil) is electrically separate from the high-power circuit. Furthermore, the user or control device can operate the contactor remotely and safely without handling high currents directly.

Do contactors make noise during operation?

Yes, many power contactors make a clicking or humming sound when the coil energizes and the contacts move.

The sound is normal and comes from the magnetic action. Excessive buzzing, though, may indicate loose laminations, coil issues, or the wrong voltage being applied to the coil.

What are the common causes of contactor failure?

Failures often come from overheating, dust build-up, or contacts wearing out due to arcing. Using a contactor beyond its rated load is another reason.

In some cases, poor ventilation or voltage fluctuations damage the coil. Preventive maintenance and choosing the right types of contactors helps avoid these problems.