PT-100 sensors are widely used for temperature measurement. They are highly accurate and reliable in industrial applications. PT-100 belongs to the resistance temperature detector family.

Its resistance changes proportionally with temperature variations. Industries rely on PT-100 for critical process control systems. These sensors operate in hazardous and safe environments alike. PT-100 is easy to integrate, durable and most importantly, is simple.

It provides precise temperature readings over a wide range. Maintenance is minimal due to its robust design.

PT-100 can measure extreme temperatures effectively. They are preferred over thermocouples in many applications.

PT-100 sensors enable better process efficiency and safety. This article reviews PT-100, its working principle, and applications.

What is PT-100?

The name PT100 reveals its core technical specs. “PT” stands for the metal platinum inside it.

A PT-100 is a type of RTD sensor, in which the RTD signifies Resistance Temperature Detector. PT indicates platinum as the sensing material.

100 refers to resistance in ohms at 0°C. Its resistance rises with increasing temperature. Platinum is chosen for stability and linearity.

PT-100 sensors can operate from -200°C to 850°C. They are more accurate than thermocouples in low ranges. Industries like chemical and food use PT-100 extensively.

Construction of PT-100

PT-100 has a platinum wire or film element. The element is wound or deposited on a ceramic.

Ceramic or glass provides electrical insulation. The sensor is protected with a stainless steel sheath.

The sheath allows insertion into pipes or tanks. Insulating materials prevent short circuits inside the sensor.

Lead wires connect the sensor to measuring instruments. Three types of configurations are available in PT-100, which are two, three, or four connecting wires.

Types of PT-100 Sensors

There are mainly three PT-100 sensor types. First is the wire-wound type for high accuracy.

Second is the thin-film type, cost-effective and compact. Third is a coiled element, flexible for small spaces.

The two-wire PT-100 is the simplest and least precise. Three-wire PT-100 compensates for lead resistance.

Four-wire PT-100 offers the highest accuracy in measurements. Selection depends on accuracy, installation, and budget.

Working Principle

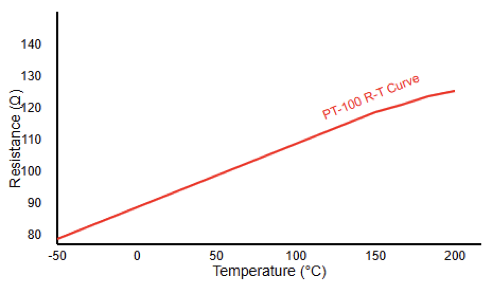

PT-100 operates based on the resistance-temperature relationship. Platinum resistance grows proportionally as temperature rises.

The resistance at 0°C is 100 Ohms, and the temperature coefficient is around 0.00385 Ω/Ω/°C.

Measuring resistance allows calculation of sensor temperature. External circuits measure the voltage across PT-100. Instruments convert voltage into readable temperature values.

The sensor does not produce its own voltage. PT-100 provides continuous and stable temperature monitoring.

The Linear Coefficient of Platinum

Scientists use a specific value called “Alpha.” For most PT100s, Alpha is 0.003851. This represents the change in resistance per degree. Every degree Celsius adds 0.3850 Ohms of resistance.

This linear behavior simplifies the math for controllers. You do not need complex curves for calculation.

Small changes in heat create measurable electrical shifts. This allows for extremely precise temperature control.

PT-100 Calibration

Calibration ensures accurate temperature readings. Sensors are compared against standard reference thermometers.

Ice point (0°C) and boiling point (100°C) calibrations are common. Three-point calibration improves accuracy further.

Calibration adjusts measuring instruments, not the sensor itself. Regular calibration maintains sensor precision over time.

Industrial standards recommend calibration frequency annually. Calibration data helps in process quality control.

Configuration Methods

PT-100 can be connected in several ways. A two-wire connection is the simplest, with two leads.

The resistance of wires affects measurement accuracy. A three-wire connection compensates for lead resistance automatically.

A four-wire connection is most accurate, ideal for precise applications. Instruments measure voltage across two opposite leads.

Connections are chosen based on distance and the accuracy required. Proper connection ensures reliable temperature readings.

Two-Wire PT100 Configuration

The 2-wire setup is the most basic style. It uses two leads to connect the sensor. It does not account for wire resistance.

This leads to inaccurate readings over long distances. You should only use it for short runs.

Or use it where high precision is unnecessary. It is the cheapest option for simple tasks. Most industrial users avoid this specific configuration.

Three-Wire PT100 Configuration

The 3-wire setup is the industrial standard today. It adds a third wire to the circuit. Two wires carry the main excitation current. The third wire acts as a sense lead. The bridge circuit calculates the lead resistance.

It then subtracts that value from the total. This removes the error caused by the cable. It balances accuracy with cost and complexity. Because of this issue, most PLCs are designed for 3-wire inputs.

Four-Wire PT100 Configuration

The 4-wire setup provides the highest precision possible. It is mainly used in laboratory environments.

Two wires provide a constant current source. The other two wires measure the voltage drop.

Since no current flows through the sense leads, resistance is zero. This eliminates all lead wire errors.

It is the gold standard for calibration work. However, it requires more expensive cabling and inputs.

Signal Conditioning

PT-100 requires signal conditioning before processing. The voltage drop across the sensor is small.

Instrumentation amplifiers enhance small signals. Wheatstone bridge configuration improves measurement accuracy.

Analog-to-digital converters digitize the sensor signal. Signal conditioners filter noise and interference.

Accurate conditioning ensures precise process control. Some systems use transmitters to convert signals. Transmitters provide standard output like 4–20 mA.

Tolerance Classes and Accuracy

PT100 sensors come in different accuracy grades. These are known as “Tolerance Classes.” Class B is the standard industrial grade. It has an error of ±0.3°C at zero.

Class A is much more precise. It offers an error of only ±0.15°C. There are also 1/10th DIN ultra-precise sensors. Better accuracy usually means a higher price tag. Always check your process requirements before buying.

PT100 vs. Thermocouples

There has always been confusion between PT100s and thermocouples. Thermocouples measure the voltage generated by two metals. They are faster and handle higher heat. However, PT100s are far more stable over time.

They do not drift as much as thermocouples. PT100s provide much better accuracy at lower ranges.

If you need precision, choose the PT100. If you need extreme heat, choose thermocouples.

Applications of PT-100

PT-100 is widely used in many industries. Chemical plants monitor the temperature of reactors.

Food industries control cooking or freezing processes. HVAC systems maintain comfortable indoor conditions.

Pharmaceutical industries monitor incubators and storage rooms. Power plants measure boiler and turbine temperatures.

PT-100 is suitable for laboratory experiments. Industrial automation systems rely on PT-100 readings.

Advantages of PT-100

PT-100 is accurate and reliable for temperature measurement. It has high repeatability over a wide range.

Long-term stability reduces maintenance requirements. Platinum material ensures chemical and corrosion resistance.

Sensor responds quickly to temperature changes. Available in various designs for different environments.

Can integrate with PLCs and control systems easily. Cost-effective for high-accuracy applications in industry.

Limitations of PT-100

If there is the existence of mechanical vibrations and shocks, the PT-100 becomes sensitive to them.

High initial cost compared to thermocouples. Requires careful wiring to avoid errors. Limited maximum temperature compared to some thermocouples.

Signal conditioning is needed for long distances. Fragile thin-film sensors may break easily.

Maintenance in harsh conditions may still be required. Proper installation avoids most limitations.

How to Test a PT100

A PT100 can be tested by using a multimeter. Set the meter to the ohms setting. Join the probes with the sensor terminals.

At room temperature, it should read Ohms. At zero degrees, it must read Ohms. If the reading is infinite, it is broken. If the reading is zero, it is shortened. This simple test confirms the sensor is healthy.

Key takeaways: What is PT-100, and how does it work?

This article demonstrated PT-100 sensors and their working principle. PT-100 provides accurate and stable temperature measurement.

Its construction, types, and wiring influence performance. Calibration and signal conditioning improve precision further.

Industries rely on PT-100 for critical process monitoring. Proper installation ensures long sensor life and reliability.

PT-100 remains a standard in modern industrial applications. They offer consistent performance in harsh environments.

Sensor selection depends on accuracy and application needs. PT-100 contributes to automation and safety in industries.

Future technologies may enhance PT-100 integration with smart systems. Overall, PT-100 is essential for precise and reliable temperature measurement worldwide.

FAQ: What is PT-100, and how does it work?

What does PT-100 mean?

PT refers to platinum. Material used to build the sensor. And 100 refers to 100 Ω resistance at 0 °C.

What type of sensor is a PT-100?

It is a Resistance Temperature Detector (RTD). It measures temperature by monitoring resistance changes.

How does a PT-100 measure temperature?

Platinum resistance rises as temperature increases. The resistance change follows a standardized curve.

What is the temperature-resistance relationship?

At 0 °C, the sensor reads 100 Ω, while at 100 °C, the resistance is about 138.5 Ω.

Why is platinum used?

Platinum provides high accuracy and stability. It is chemically stable and reproducible over time.