Industrial systems are becoming more connected. They are also more data-driven and intelligent.

Traditional automation architectures rely on local control. They often use isolated networks. These approaches struggle with modern complexity.

Scale and speed are also limiting factors. Industrial cloud computing addresses these challenges.

It combines cloud technologies with industrial automation systems. This enables scalable storage and advanced analytics.

It also supports remote access and system integration. Industrial cloud computing extends classical automation.

Smart manufacturing, as well as the Industry 4.0 initiative, is supported. This article explains the concept. It also covers architecture, components, use cases, benefits, and challenges.

Definition of Industrial Cloud Computing

Industrial cloud computing applies cloud technologies to industrial environments. These technologies include infrastructure, platforms, and software. Delivery is provided over the internet. Industrial environments include factories and utilities.

They also include oil, gas, and water facilities. Industrial data has unique characteristics. Real-time behavior is often required.

Reliability expectations are high. Asset lifecycles are long. Safety and cybersecurity constraints are strict.

Industrial cloud systems address these needs. They integrate operational technology with information technology. This bridges factory-floor devices and enterprise systems.

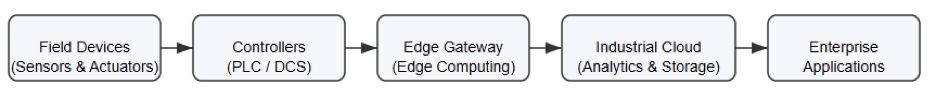

The next figure indicates a diagram of industrial cloud architecture. It shows field devices, controllers, edge gateways, industrial clouds, and enterprise applications.

From Traditional Automation to Cloud-Based Systems

Historically, automation systems were isolated. Architectures were hierarchical. Sensors connected to PLCs or DCS controllers.

These systems are linked to HMI or SCADA platforms. Data was stored locally. Access was limited and proprietary.

IIoT technologies changed this model. Ethernet networks became common. Standard protocols improved interoperability.

Cloud computing added scalable resources. Storage and computing power became virtually unlimited. Organizations could centralize analytics and visualization.

Industrial cloud computing complements local control. It does not replace it. Real-time control remains on-site. Data-heavy tasks move to the cloud. This balances performance and flexibility.

Core Components of Industrial Cloud Computing

Industrial Devices and Control Systems

At the lowest level are field devices. These include sensors and actuators. Drives and soft starters are also present. PLCs and DCS controllers manage control logic.

These devices generate raw operational data. Examples include temperature and pressure. Electrical and status signals are common.

Edge Computing and Gateways

Edge devices sit between the plant and the cloud. They aggregate and preprocess data. Filtering and local analytics are performed. Deterministic behavior is preserved. Latency is reduced. Bandwidth usage is optimized.

System resilience improves. The upcoming figure illustrates a diagram of edge computing with local analytics before cloud transmission.

Cloud Infrastructure

The cloud layer provides scalable resources. It includes computing and databases. Networking services are also provided. Historical data is stored here. Advanced analytics are executed.

Machine learning models are supported. Deployment can be public or private. Hybrid options are also common.

Applications and Services

Cloud applications sit at the top layer. These include dashboards and asset management tools. A large number of uses exist out there.

Predictive maintenance, also known as PdM, is a vivid example. In addition, the management of energy platforms is included. Digital twins are also supported. Raw data becomes actionable insight.

Service Models in Industrial Cloud Computing

The Infrastructure as a Service

Also known as IaaS. Once well studied and understood, IaaS provides virtual infrastructure. Computing and storage are included.

Networking is also available, and industrial users host historians and data lakes. Physical servers are no longer required.

Platform as a Service

Shortly, PaaS supports application development. It includes databases and middleware. Data ingestion tools are provided. Analytics and visualization are simplified. Development time is reduced.

Software as a Service

This is a cloud-based model where software is centrally hosted and delivered to users. The whole process occurs over the internet, usually via a web browser, on a subscription basis, eliminating the need for local installation and maintenance. It is also called SaaS; it delivers ready-made applications.

Access is provided through web interfaces. Condition monitoring is a common example. Production reporting is also included. Remote asset management is supported.

Deployment Models

Public Industrial Cloud

Public clouds are provider-managed. Resources are shared across customers. Scalability is high. Upfront costs are low. Data sovereignty may be a concern. Security requirements must be evaluated.

Private Industrial Cloud

Private clouds serve one organization. Control and customization are greater. Critical infrastructure benefits from this model. Regulatory compliance is easier.

Hybrid and Multi-Cloud

Hybrid models combine local systems and cloud services. Multi-cloud uses several providers.

Vendor lock-in is reduced. Resilience is improved. The following figure depicts a hybrid cloud linking on-premises systems with public and private clouds.

Use of Industrial Cloud Computing

Predictive Maintenance

Cloud analytics processes operational data. Failure patterns are identified early. Maintenance becomes proactive. Downtime is reduced. Costs are lowered.

Remote Monitoring and Operations

Assets can be monitored remotely. Engineers access systems from anywhere. Distributed facilities benefit greatly. Examples include pipelines and substations.

Energy Management

Energy usage is tracked centrally, and inefficiencies are identified. Data-driven is obviously a result of optimization. Multi-site visibility is achieved.

Quality and Process Optimization

Analytics detect process deviations. Quality issues are identified early. Continuous improvement is supported.

Benefits of Industrial Cloud Computing

Industrial cloud systems scale easily. Infrastructure investment is reduced. Decisions become data-driven.

Collaboration improves through centralized data. Remote access increases flexibility. Response time is reduced. Innovation accelerates.

Advanced tools like artificial intelligence (AI) are enabled. Without forgetting digital twins, as mentioned.

Challenges and Considerations

Latency must be controlled carefully. Time-critical functions need protection. Reliability is essential.

Cybersecurity is a major concern. Strong authentication is required. Encryption and segmentation are necessary.

Legacy integration can be complex. Regulatory and data ownership issues must be addressed.

Security in Industrial Cloud Computing

Industrial cloud security extends beyond IT. OT-specific threats must be addressed. Unauthorized control is a risk. Process manipulation is possible.

Defense-in-depth is commonly used. Secure devices are configured first. Networks are segmented. Communications are encrypted. Access is tightly controlled.

Future Trends

Industrial cloud adoption continues to grow. Digital twins are becoming widespread. Virtual factories are being developed.

Advanced optimization is emerging. New computing paradigms are explored. Cloud integration remains central to Industry 4.0. Smart factories depend on it. Asset lifecycle management improves.

Key Takeaways: Industrial Cloud Computing

This article addressed industrial cloud computing and its role. Architecture and service models were explained.

Deployment options and use cases were reviewed. Industrial cloud computing enhances traditional automation.

It provides scalable storage and analytics. Global connectivity is enabled. Challenges must be managed carefully. Cybersecurity and latency are critical factors. Legacy systems require attention.

Despite this, the benefits are substantial. Industrial cloud computing supports digital transformation. It enables smarter and more efficient operations.

FAQ: Industrial Cloud Computing

What is industrial cloud computing?

It is the use of cloud computing technologies to store, process, and analyze industrial data from machines and processes.

How is it different from traditional cloud computing?

It is designed for industrial environments and integrates with automation systems and real-time operational data.

What industries use industrial cloud computing?

Manufacturing, energy, utilities, oil and gas, transportation, and water treatment.

What problems does it solve?

It improves visibility, reduces downtime, enables remote monitoring, and supports data-driven decisions.

What are common use cases?

Predictive maintenance, asset monitoring, energy management, and process optimization.

Does it replace PLCs or DCS systems?

No. It complements them by handling analytics, storage, and enterprise integration.

What role does edge computing play?

Edge computing processes data locally before sending relevant information to the cloud.

What are the main benefits?

Scalability, centralized data, advanced analytics, and remote access.

What are the main challenges?

Cybersecurity, latency, legacy system integration, and regulatory compliance.

Is industrial cloud computing part of Industry 4.0?

Yes. It is a key enabler of Industry 4.0 and digital transformation.