In current motion control within automation systems, encoders play a critical role. They are essential devices in modern automation and control systems. They convert mechanical motion into electrical signals.

These signals are then interpreted by controllers, drives, or monitoring systems. Encoders are widely used in industrial machinery and robotics.

They are also found in CNC machines, elevators, and renewable energy systems.

Accurate position and speed feedback is critical in these applications. Different encoder types exist to meet different accuracy and speed requirements. Also, to meet environmental requirements, which are essential.

There are different types of encoders. Understanding encoder types is important for choosing the correct device for a specific task.

This article explains the main types of encoders by comparing their working principles, advantages, and applications.

Understanding Encoder

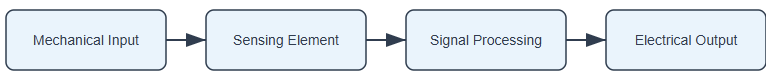

An encoder is a feedback sensor that detects motion. Motion can be rotational or linear. The encoder converts this motion into digital or analog signals.

These signals represent position, speed, direction, or distance. Controllers use this data for precise control.

Encoders improve accuracy and repeatability. They are critical in closed-loop control systems.

Classification of Encoders

Encoders can be classified in several ways. The most common classifications are based on motion type and output type. Each classification addresses a specific application need.

The main categories are rotational and linear encoders. Another major division is incremental and absolute encoders. Encoders can also be classified by sensing technology.

Rotational Encoders

Rotational encoders measure angular position or speed. They are mounted on rotating shafts.

They are common in motors and gear systems. Rotational encoders are used in conveyors, servo motors, and pumps.

Optical Rotational Encoders

Optical encoders use light for sensing. A coded disk is attached to the shaft, and a light source shines through the disk. Photodetectors receive the light. Slots or patterns on the disk interrupt the light.

The output depends on disk rotation. High resolution is possible. Optical encoders are very accurate. They are sensitive to dust and moisture.

Magnetic Rotational Encoders

Magnetic encoders use magnetic fields. A magnet is attached to the shaft, and a magnetic sensor detects field changes. Hall-effect or magneto-resistive sensors are common.

These encoders are robust due to their tolerance to dust and vibration. Resolution is lower than optical types. They are ideal for harsh environments.

Linear Encoders

Linear encoders measure straight-line motion. They are used in machine tools and positioning systems. They provide direct measurement of displacement.

Optical Linear Encoders

Optical linear encoders use a scale and a read head. The scale has fine markings. Light passes through the scale, and the read head detects movement.

They provide very high accuracy. CNC machines are the common use. To take advantage of them, clean environments are required.

Magnetic Linear Encoders

Magnetic linear encoders use a magnetic strip. A sensor reads magnetic transitions. These kinds of encoders are less sensitive to contamination.

They are easier to install, and their accuracy is moderate. They are common in industrial automation.

Incremental Encoders

These encoders rely on pulse generation. This means incremental encoders generate pulses when motion occurs.

They do not store absolute position. Position is determined by counting pulses. If power is lost, the position is lost.

Incremental encoders are simple. They are cost-effective. This is why they are widely used in speed measurement.

Working Principle

When the shaft rotates, pulses are generated. Each pulse represents a fixed movement. Two output channels are usually provided.

These are called A and B, and they are phase-shifted. The phase shift indicates direction. A third channel may exist. It is called the index or Z channel and provides a reference position.

Advantages and Limitations

They are simple to use. They have high-resolution options and are affordable. They are suitable for speed control.

Position is lost on power failure, so homing is required after restart. External counters are needed.

Absolute Encoders

Absolute encoders provide a unique position value. Each position has a distinct code. Position is retained after power loss.

In this case, no homing is required. Absolute encoders are used where safety and accuracy are critical. They are common in robotics and cranes.

Single-Turn Absolute Encoders

Single-turn encoders measure position within one rotation. The output resets after one revolution.

Each angular position has a unique code. They are used in valve positioning. They are very common in servo systems.

Multi-Turn Absolute Encoders

Multi-turn encoders track multiple rotations. They store the rotation count internally. Mechanical gears or electronic counters are used, and they provide full position information. The main use is in elevators and wind turbines.

Encoder Output Types

Encoders differ in output format. Output type affects compatibility and noise immunity. Encoder output types describe the electrical signal format, with the most common being Open Collector.

Also, Push-Pull (Totem Pole/HTL)and Differential Line Driver (TTL). Each is suited for different applications and noise levels.

They convert position/motion into digital signals like pulses (incremental) or unique codes (absolute) for PLCs.

It may also include microcontrollers. Voltage levels and current sourcing/ or sinking capabilities are the main keys for their differentiation.

Digital Encoders

Digital encoders produce pulses or binary data. Incremental and absolute encoders fall into this category.

The digital outputs are always robust. Plus, they are really easy to interface with PLCs. Common interfaces include TTL, HTL, and RS-422.

Analog Encoders

Analog encoders produce continuous signals. Output may be voltage or current. Examples include 0–10 V or 4–20 mA. They provide smooth position feedback. Their resolution is lower, and they are sensitive to noise.

Contact and Non-Contact Encoders

Encoders can also be classified by sensing contact.

Contact Encoders

Contact encoders use physical contact. Potentiometer-based encoders are examples. A wiper moves along a resistive track. They are simple and inexpensive. Wear occurs over time, and accuracy degrades.

Non-Contact Encoders

Non-contact encoders use optical or magnetic sensing. There is no mechanical wear. Lifespan is longer, and accuracy is higher. Most modern encoders are non-contact types.

Capacitive Encoders

Capacitive encoders detect changes in capacitance. A patterned scale is used. Movement changes the electric field.

They offer good resolution and are immune to magnetic fields. They are sensitive to humidity and contamination. Commonly, they are used in precision instruments.

Inductive Encoders

Inductive encoders use electromagnetic induction. A conductive scale interacts with coils. Position is detected through signal changes.

They are extremely robust. Since they tolerate oil and dirt, the accuracy is moderate. They are popular in heavy industrial environments.

Resolver as a Special Encoder Type

Resolvers are analog rotary position sensors. They resemble rotary transformers. Output signals are sine and cosine waves.

Resolvers are very robust, and they operate in extreme temperatures. In this type, signal processing is complex. They are used in aerospace and military systems.

Comparison of Encoder Types

Different encoder types suit different needs. Optical encoders offer high precision. Magnetic encoders offer durability.

While incremental encoders are simple and fast. On the other hand, absolute encoders provide safety and reliability.

Also, linear encoders provide direct position measurement. Plus, rotational encoders measure angular motion. The environment often dictates the choice.

Applications of Encoders

Encoders contain a vast number of applications. A few are briefly explained below

· Robotics: Encoders are used for precise joint position and motion control.

· CNC machines: They provide accurate axis positioning and feedback.

· Conveyor systems: Encoders are applied for speed monitoring and control.

· Elevators: Absolute encoders are relied upon for safe and accurate position detection.

· Renewable energy systems: Encoders are used for blade and pitch positioning.

· Packaging machines: Precise synchronization depends on encoder feedback.

Selecting the Right Encoder

When choosing an encoder in the market, engineers must weigh several competing factors. One key factor is resolution requirements.

This defines how many counts per revolution are needed for accurate measurement. A precision lathe may require around 10,000 pulses per revolution.

A simple garage door system may function well with only 100 pulses. Mounting space is another important consideration. Some applications have very limited physical space.

This is common in small drone motors and compact actuators. In such cases, magnetic or capacitive kit encoders are preferred. They offer a very low profile and flexible integration.

Safety integrity level is also critical. Currently, safety-rated encoders are mandatory for human-collaborative robots. These encoders include redundant internal circuits.

The redundancy prevents runaway motion if one internal component fails. This greatly improves system safety and reliability.

Conclusion

This article dealt with the main types of encoders. It explained their working principles, advantages, and applications. It also addressed the selection criteria. Encoders are vital components in motion control systems.

Encoders are no longer just sensors; they are the fundamental data source for the physical world.

They provide accurate feedback for position, speed, and direction. Many encoder types exist. Each type serves a specific purpose.

For instance, incremental encoders are simple and economical. Absolute encoders provide reliable position data.

Optical encoders offer high precision. Magnetic and inductive encoders provide durability.

Linear and rotational encoders address different motion types. Proper encoder selection must be taken into account.

This is because it improves system performance and reliability. Efficient and safe automation systems can be designed if engineers understand encoder types.