The Internet of Things (IoT) is a rapidly growing field. It has changed the landscape of engineering in many significant ways.

IoT refers to a vast network of physical devices, often called “things,”. The latter are equipped with sensors, software, and other technologies.

These devices connect with other systems and exchange data over the internet. For engineers, IoT is not just about linking devices. It is about creating fully connected systems that collect real-time data.

It also enables automation and intelligent decision-making. IoT combines multiple engineering disciplines. These include computer science, electrical engineering, and mechanical engineering.

It has become a key driver of innovation in a wide variety of industries. This article explains how IoT functions in engineering, its components, applications, challenges, and emerging trends for the future.

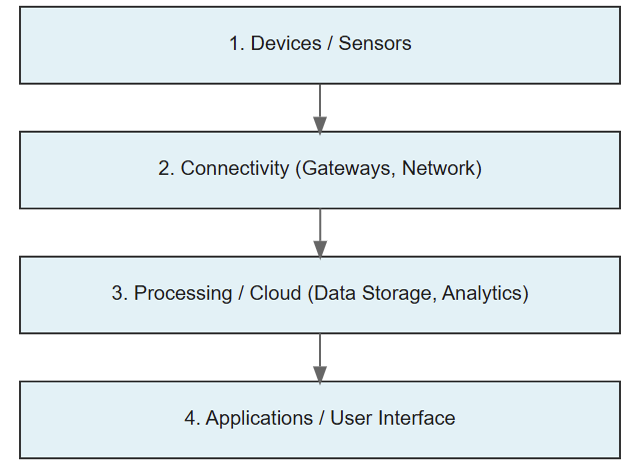

The core components of an IoT system

An IoT system, especially in engineering, is composed of several interconnected components. These components work together to gather, process, and act on data effectively.

Devices and Sensors

Devices are the physical “things” in an IoT system. They are embedded with sensors and actuators to measure and interact with the environment. Sensors can detect temperature, pressure, vibration, or movement.

Actuators allow devices to respond to conditions in real time. In engineering, examples include sensors on a factory floor that monitor machinery health. They are also used in smart grids to track energy usage.

Connectivity

This layer enables data to flow from devices to networks and back. Multiple communication technologies are used for this purpose.

Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, cellular networks (4G and 5G), and low-power wide-area networks (LPWAN) like LoRaWAN are common.

The choice of connectivity depends on specific application requirements. Engineers must consider range, bandwidth, and power consumption when selecting a technology.

Data Processing and Analytics

Data collected from devices is sent to cloud systems or processed at the edge. Edge computing allows data processing near the source, which reduces latency. Cloud computing offers scalable storage and processing for large datasets.

Advanced analytics, including AI and machine learning, extract insights from the data. These tools identify patterns and support informed engineering decisions.

Application and User Interface

This layer provides an interface for users to manage IoT devices. It can be a web or mobile application. Engineers use it to monitor systems and visualize data through dashboards. They can also control devices remotely using this layer.

The next figure shows a simple diagram of four-layer IoT architecture. It indicates data flow from devices/sensors through connectivity. Furthermore, a processing/cloud, and applications/user interface.

Applications of IoT in engineering

IoT is transforming engineering practices across many sectors. It enhances efficiency, productivity, and innovation.

Electrical and electronics engineering

IoT merges hardware, software, and networking for more intelligent electrical and electronic systems.

- Smart Grids: IoT-enabled smart meters and sensors measure energy consumption and power quality in real time. Engineers use this data to optimize distribution. They reduce energy waste and manage power usage efficiently.

- Renewable Energy: IoT monitors systems such as solar panels and wind turbines. Sensors track output and performance. Engineers can optimize operations and conduct predictive maintenance on renewable energy assets.

- Home and Building Automation: Electrical and electronics engineers design smart systems for buildings and homes. These systems automate lighting, HVAC, and security. Automation improves energy efficiency and convenience for occupants.

Industrial engineering and manufacturing

In industrial contexts, IoT is often called the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT). It is revolutionizing manufacturing processes.

Sensors and smart devices optimize operations. They improve product quality and ensure safety in the workplace.

- Predictive Maintenance: IoT sensors continuously monitor machinery. Parameters such as temperature and vibration are recorded in real time. The data is analyzed to predict potential equipment failures. This allows proactive maintenance. Engineers can reduce costly unplanned downtime by addressing issues before they become severe.

- Asset Tracking and Management: RFID tags and GPS trackers are applied to equipment, tools, and inventory. These devices provide real-time location data. This improves supply chain efficiency and prevents misplacement of assets. Logistics operations are streamlined and become more accurate.

- Quality Control: IoT-enabled cameras and sensors continuously monitor production lines. They detect defects and ensure products meet quality standards. This automated approach is more precise than manual inspection.

- Worker Safety: Wearable devices and environmental sensors monitor the workplace. They alert workers to potential hazards. This contributes to safer working conditions in industrial environments.

Mechanical engineering

Mechanical engineers use IoT to improve design, reliability, and maintenance of products.

- Digital Twin Technology: IoT powers digital twin technology. A virtual copy of a physical object is created and updated with real-time sensor data. Engineers can test and optimize designs in a virtual environment. They can predict performance and identify issues without building physical prototypes.

- Remote Control: IoT enables remote monitoring and control of mechanical components. Pumps, valves, and motors can be operated from a distance. This ensures proper function and simplifies troubleshooting.

- Field Testing: Sensors in prototypes collect real-time data during field tests. Engineers can quickly identify and fix problems. This improves product quality, reliability, and overall performance.

Civil and infrastructure engineering

IoT is crucial for monitoring and managing infrastructure. It ensures safety, efficiency, and sustainability in civil projects.

- Smart Cities: Engineers use IoT in smart city projects to manage urban systems efficiently. Traffic management systems adjust signal timings based on real-time traffic data. Smart lighting systems modify illumination according to ambient light levels. Waste management systems use sensors to detect when bins are full.

- Structural Health Monitoring: Sensors embedded in bridges, buildings, and other structures monitor integrity continuously. They detect cracks, shifts, or corrosion. Engineers receive alerts about potential issues before they develop into major failures.

- Water Management: Smart sensors monitor water quality and track consumption. They detect leaks in pipelines. This allows better water conservation and more effective distribution management.

Challenges of IoT in engineering

Despite its advantages, IoT integration faces several challenges. Security and privacy are major concerns.

Many IoT devices have minimal built-in protection. They are vulnerable to cyberattacks, malware, and data breaches.

This risk is especially critical for infrastructure systems, where a breach could have serious physical consequences.

Another challenge is interoperability and standardization. The lack of universal standards creates issues in communication between devices. Products from different manufacturers may not work seamlessly together.

Engineers must carefully plan integration to ensure all components function smoothly within the system.

Data management is also a significant challenge. IoT devices generate massive volumes of data at high speed.

Managing, storing, and analyzing this data requires robust strategies and advanced analytics tools.

Without proper management, valuable insights may be lost, and system performance can suffer.

The complexity and scalability of IoT systems increase as networks grow. Systems must handle larger numbers of devices, higher data volumes, and more functional requirements. Maintaining performance and scalability while managing this complexity can be difficult.

Finally, cost and implementation are important considerations. Setting up IoT systems involves investment in hardware, software, and supporting infrastructure.

Integration with existing systems can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, making initial deployment expensive and challenging.

The future of IoT in engineering

The future of IoT in engineering is shaped by advancing technologies and the increasing demand for smart solutions.

AIoT and AI-driven automation are key developments. Combining AI and IoT, known as AIoT, enables intelligent and autonomous systems.

AI algorithms can process IoT data for predictive maintenance, autonomous vehicles, and automated decision-making without human intervention.

Edge and fog computing are becoming more important to reduce latency. Data processing is moving closer to the source.

This reduces dependence on cloud systems for critical applications and improves response times.

The use of digital twins is expected to expand beyond manufacturing. Engineers will apply digital twins in infrastructure projects and urban planning.

These virtual models allow them to simulate complex systems before implementing physical changes.

5G connectivity will play a crucial role in the next generation of IoT applications. High-speed, low-latency networks can support large numbers of devices. This enables real-time data transfer and ensures more reliable and responsive systems.

Finally, enhanced security will be critical as IoT adoption grows. Stronger device authentication, data encryption, and strict security protocols will be necessary to protect systems from cyber threats.

.

Key Takeaways: What is IoT in Engineering?

This article explored how IoT impacts engineering, its challenges, applications, and the technologies shaping its future. Therefore, we can say that IoT connects the physical and digital worlds.

It enables real-time data collection, automation, and intelligent control. Engineers across multiple disciplines, industrial, civil, electrical, and mechanical, can design systems with greater efficiency and reliability.

Security, interoperability, and data management remain challenges. Advances in AI, edge computing, and 5G are creating more sophisticated and integrated IoT solutions. For engineers, understanding and adopting IoT is essential.

It is not just about keeping up with technology. It is about driving innovation and creating a smarter, more connected world.

FAQ: What is IoT in Engineering?

What is IoT in engineering?

It refers to the integration of internet-connected sensors, devices, and systems into engineering processes and infrastructure.

These networks collect, exchange, and analyse data to enable real-time monitoring, automated action, and smart decision-making.

Why is IoT important for engineering?

Because it helps engineers bridge the physical and digital worlds. It enables systems to become more efficient, productive, and responsive.

It also supports innovation in fields like manufacturing, infrastructure, energy, and product design.

What are the key components of an IoT system in engineering?

The main components include: devices and sensors (to measure and act), connectivity (to transmit data), data processing and analytics (cloud or edge), and applications/user interface (to monitor and control).

What are common engineering applications of IoT?

Examples include: predictive maintenance for machinery, smart asset tracking in factories, structural health monitoring for bridges and buildings, smart grids in electrical engineering, and digital-twin models in mechanical engineering.

What are some major challenges when implementing IoT in engineering?

Major challenges include security & privacy risks, interoperability and standardization issues, managing large volumes of data, complexity and scalability of systems, and high cost-plus difficult implementation.

How does IoT relate to Industry 4.0?

IoT is a key enabler of Industry 4.0: it allows manufacturing and industrial processes to become smart, connected, and data-driven.

It helps link operational technology (OT) and information technology (IT) for improved visibility and control.

What trends are shaping the future of IoT in engineering?

Some upcoming trends are: AIoT (combining AI with IoT), edge/fog computing (processing data closer to the source), digital twin expansion, 5G connectivity, and stronger security measures.

How can an engineer prepare to work in IoT?

Engineers should develop cross-disciplinary skills: hardware (sensors/actuators), software (embedded systems, cloud), networking (communication protocols), data analytics, and security.

They should also stay abreast of emerging connectivity technologies, standardization, and system integration strategies.

Is IoT just for technology companies or for all engineers?

IoT is relevant across all engineering disciplines mechanical, electrical, civil, manufacturing, etc.

Technologies and systems embedded with sensors and connectivity are increasingly part of many engineering fields.

Hence, many engineers are expected to understand IoT principles, not just specialists.

What are the benefits of IoT in engineering?

Benefits include real-time monitoring, automation, predictive decision-making, improved asset utilization, enhanced safety, reduced downtime, and innovation in products and systems.