A level sensor is a device that determines the height or amount of material inside a container or system. The material can be liquid, powder or granular.

Accurate level measurement is vital for maintaining safety, ensuring quality control, and improving operational efficiency.

It is widely used across many industrial processes. Generally, level sensors are divided into two main types: point level and continuous level measurement. Point level sensors detect when the material reaches a specific level.

While continuous level sensors, on the other hand, measure the actual height of the material in real time.

The correct choice of sensor depends on several factors, including the application, material characteristics and required accuracy.

This article describes the main types of level sensors and explains how each one works.

Point Level Measurement

As mentioned above, point-level sensors are designed to show whether a material has reached a particular point.

They function like switches, providing an “on” or “off” signal. These sensors are commonly used for overflow or low-level alerts, preventing tanks from overfilling or running dry. They are simple, low-cost, and easy to install.

Float Switches

Float switches operate based on buoyancy. A float sits on the liquid surface and moves up or down as the level changes.

This movement activates a switch, often magnetically, to open or close an electrical circuit.

Float switches are affordable and dependable, but they include moving parts and can be large. They are not ideal for sticky or corrosive liquids that could cause buildup on the float.

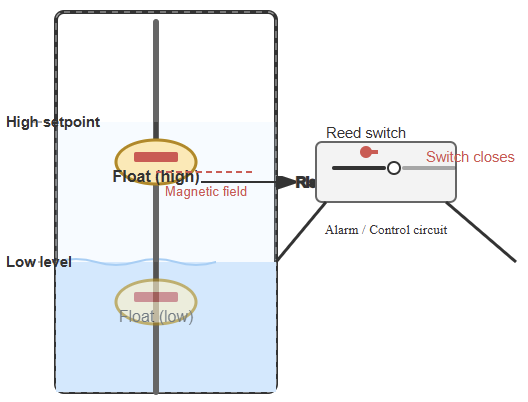

The following figure indicates a diagram illustrating a float switch showing a float moving with the liquid level in a tank.

The float mechanically activates a switch (e.g., a reed switch) at a specific high or low point. So, this figure helps visualize the mechanical operation of a float switch.

Optical Level Sensors

Optical level sensors rely on light to sense liquid presence at a fixed point. They contain an infrared LED and a photodetector in the sensor tip. In air, the light reflects internally and reaches the receiver.

When submerged, the light is refracted into the liquid, reducing the signal received. This change triggers a switch output. These sensors are compact and have no moving parts but may be affected by dirt or film on the lens.

Conductivity Level Sensors

Conductivity (or resistance) sensors use a probe with two or more electrodes. A low-voltage AC current flows between them. When a conductive liquid covers the electrodes, the circuit closes and current passes, indicating level detection.

These sensors are simple and inexpensive but only work with conductive liquids, and electrode wear can occur over time.

Vibrating (Tuning Fork) Level Sensors

These sensors include a fork-shaped element that vibrates at a set frequency. When liquid or solid material touches the fork, its vibration frequency changes. The electronics detect this change and switch the output.

Vibrating sensors are reliable, unaffected by temperature or conductivity, and require little maintenance. However, they must come into contact with the medium to function.

Continuous Level Measurement

Continuous level sensors provide ongoing measurement of the material height or volume. They produce a variable signal (such as 4–20 mA or digital) that represents the actual level. These sensors are more advanced and generally costlier than point-level types.

Ultrasonic Level Sensors

Ultrasonic sensors use sound waves to measure distance without contact. Mounted above the tank, they send high-frequency pulses toward the material surface. The sound reflects back to the sensor.

The time taken for the echo to return (time-of-flight or ToF) is then used to calculate the distance. From this, the level is determined. They are well-suited for corrosive liquids but can be affected by foam, vapor, or turbulence.

Then the actual distance can be calculated using the following basic formula:

The division by 2 accounts for the round trip (going to the object and returning).

The following figure depicts a diagram showing an ultrasonic sensor mounted on top of a tank. It illustrates sound waves being emitted, reflecting off the liquid surface, and returning to the sensor.

Also, it specifies the distance D and the time-of-flight t labeled. This figure illustrates the time-of-flight principle used by ultrasonic sensors.

Radar Level Sensors

Radar sensors (microwave type) use electromagnetic waves instead of sound. The antenna transmits microwaves toward the material surface, and the reflected signal returns to the sensor.

The time delay helps calculate the level. Radar sensors perform well in extreme conditions, high temperature, pressure, or dust and are unaffected by vapor. They are highly accurate and non-contact.

The upcoming figure represents a diagram showing a radar sensor emitting microwaves toward the liquid surface.

The reflections are used to compute the liquid level through time delay. The mentioned figure shows how radar waves measure level precisely.

Capacitance Level Sensors (Continuous)

Capacitance sensors measure level using changes in capacitance. The probe acts as one plate of a capacitor, and the tank wall or a second probe acts as the other. As the material rises, the dielectric constant changes, altering capacitance.

The sensor’s electronics convert this change into a level signal. These sensors are durable and have no moving parts.

Hydrostatic Pressure Sensors

These sensors measure the pressure exerted by the liquid column. The pressure at the bottom is proportional to the liquid height and density. Submersible sensors placed near the tank bottom detect this pressure.

They then generate an electrical signal that corresponds to the liquid level. They are accurate but depend on constant liquid density for precise readings.

Guided Wave Radar (GWR)

GWR sensors combine radar and contact technology. A probe (rod or cable) extends into the tank, guiding microwave pulses downward. When the pulse hits the material, part of it reflects back.

The time-of-flight determines the level. GWR sensors are very accurate and less affected by foam or turbulence than non-contact methods. This makes them reliable for challenging applications

Key takeaways: Types of Level Sensors

This article presented the different types of level sensors and their operating principles. Level sensors are fundamental components in both industrial and domestic systems. They ensure accurate monitoring, safety, and effective process control.

These sensors are generally classified into point and continuous measurement types. Point sensors, such as float, optical, conductivity, and vibrating switches, provide simple on/off detection.

They are ideal for use in alarm systems and level limit control. Continuous sensors, including ultrasonic, radar, guided wave radar, capacitance, and hydrostatic types, deliver real-time level data. They also provide precise measurements for accurate monitoring.

They are often used in automation and advanced monitoring applications. Selecting the appropriate sensor depends on factors such as the medium’s properties, tank design, temperature, and required accuracy.

Each sensor type has its own advantages and limitations. Choosing the right one is essential for achieving optimal performance and long-term reliability.

FAQ: Types of Level Sensors

What are the main types of level sensors?

Level sensors are divided into point-level and continuous-level types.

When should I use a point or continuous sensor?

Use point sensors for full/empty detection and continuous sensors for real-time monitoring.

What are examples of point-level sensors?

Float switches, optical sensors, conductivity probes, and vibrating (tuning fork) sensors.

What are examples of continuous level sensors?

Ultrasonic, radar, guided wave radar, capacitance, and hydrostatic pressure sensors.

What factors affect sensor selection?

Material type, conductivity, tank design, pressure, temperature, and required accuracy.

Can level sensors work in harsh environments?

Yes. Radar and ultrasonic sensors handle heat, pressure, and corrosive media well.

What are some drawbacks of level sensors?

Float switches can jam, ultrasonics fail with foam, and radar sensors are costly.

Do level sensors need maintenance?

Yes. Regular inspection and calibration maintain accuracy and reliability.

What outputs do continuous sensors provide?

They give analog (4–20 mA) or digital outputs like Modbus or HART.

What’s the difference between contact and non-contact sensors?

Contact sensors touch the material; non-contact sensors measure from a distance.