Losing a stored program, configuration, or operational state is a serious concern in electronics and automation.

This issue can affect microcontrollers (MCUs), Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs), and general software systems.

It often leads to downtime or data loss. The reasons vary widely, from unstable power and hardware damage to software malfunctions and corrupted memory. Understanding these causes is essential for proper troubleshooting.

PLC Loses Program – Reasons and Fixes

This article surveys the main reasons why programs fail to retain their data. It also provides practical methods to resolve them.

The aim is to help users and engineers maintain dependable and long-lasting systems.

Power Supply Issues

Power instability is one of the most frequent causes of program loss. This is especially true in industrial and embedded systems. Voltage dips (brownouts) and power surges can interrupt normal device operations.

These fluctuations can corrupt the memory that stores the program or its current state.

A sudden power cut during a data write process can prevent proper saving. This leaves the program incomplete or unreadable.

The program may appear lost when, in fact, the flash memory was never fully updated.

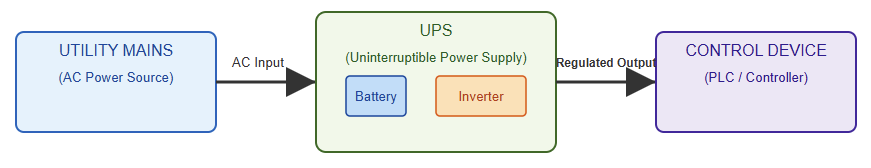

To prevent this, use a stable power source. Adding a surge suppressor or an Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS) helps regulate voltage. It also protects memory integrity.

The next figure illustrates a diagram showing a regulated power flow through a UPS connected to a control device

Hardware Faults

Defective hardware components can also cause program loss. A malfunctioning non-volatile memory chip might fail to retain data after power is turned off.

Faults in the reset circuit or a corrupted bootloader can prevent the user program from starting.

The code might still be in memory, but it cannot execute. Likewise, damaged printed circuit boards (PCBs) caused by poor soldering or mechanical stress may lead to intermittent faults.

Testing by replacing suspicious parts is a good first step. For MCU-related problems, re-flashing the correct bootloader via an In-System Programmer (ISP) can restore normal function.

Software Bugs and Errors

Programming errors can sometimes imitate program loss. For instance, a software loop or crash may freeze the system and erase its current RAM state. The stored program remains intact, but the device stops operating as intended.

Corruption of configuration files can make the system boot with default settings.

This gives the impression of data loss. Adding robust error handling, watchdog timers, and diagnostic logging (e.g., on an SD card) can help identify these issues.

Proper programming logic should ensure that data saving occurs safely before the system powers down.

Memory Corruption

Memory corruption is another common problem. Electrical noise, interference, or even cosmic radiation can flip bits in memory.

This alters stored data unexpectedly. As a result, programs may behave erratically or fail entirely.

In some cases, invalid memory addressing causes a program to overwrite its own instructions.

This destabilizes the system. Periodic memory testing and using memory with error-correcting codes (ECC) can reduce these risks.

Implementing checksums or CRC validation routines during startup helps detect and isolate corrupted sections.

Incorrect Configuration

Incorrect configuration parameters often prevent a program from starting properly.

A misconfigured I/O port can stop a PLC cycle. An incorrect boot option can stop a microcontroller from launching user code.

These problems usually arise after updates or manual adjustments. To avoid them, always review configuration settings thoroughly.

Keeping a verified backup of configuration files in a secure location helps ensure easy recovery.

Comparing stored settings with an original version after reboot confirms whether the issue is configuration-related or a true program loss.

Firmware Issues

Outdated or unstable firmware can introduce memory and power handling bugs. Certain firmware builds may fail to properly save or restore data during reboots. This leads to missing or corrupted programs.

Regularly checking for manufacturer firmware updates is crucial. Installing a tested and stable version can resolve these hidden problems.

For instance, updating the firmware on a Pi Pico running CircuitPython has been known to fix disappearing program issues.

Data Storage Failure

When programs rely on external storage, corruption or wear-out of that storage medium can cause data loss.

SD cards and USB drives may fail over time or during improper shutdowns. This results in missing configuration files or lost historical logs.

Although the main software might still run, its functionality is reduced without access to stored data.

Performing periodic backups and using high-quality, industrial-grade storage solutions minimize the risk.

The afore exhibited figure indicates a diagram showing automatic data backup from main storage to an external device.

Environmental Factors

Environmental stress can severely impact electronic devices. Overheating can degrade components.

Humidity can cause short circuits. Constant vibration can loosen connectors or damage PCBs.

Maintaining the device within its specified environmental limits is vital. Using protective enclosures, stable mounting systems, and controlled ventilation helps preserve long-term reliability, even in harsh conditions.

EMI and RFI

Electromagnetic interference (EMI) and radio frequency interference (RFI) are common in industrial environments that contain a variety of electrical equipment. Anything from handheld radio transmitters used by maintenance staff, to a large motor starting can cause interference.

Companies need to control electrical noise as much as possible, because it can lead to intermittent faults or unusual behavior and even PLC failure.

There are many ways to mitigate the risk of downtime caused by electrical noise through design.

A service engineer can recommend ways to minimize noise by relocating sensitive equipment, segregating systems with high power components and adding barriers, grounding, or shielding cable between sensitive equipment.

Debugging and Troubleshooting

A structured troubleshooting process is essential to identify the real cause of program loss.

Start by verifying if the code remains in memory after a restart. Use a programmer to read and compare memory content with the original file.

Check all voltage inputs for spikes or drops using a multimeter. Record error logs before shutdown to detect when failures occur.

This methodical approach helps narrow down whether the fault lies in power, hardware, or software. It saves both time and resources.

Managing the Risks

Prevention is more effective than repair. Schedule regular system maintenance and back up all program files frequently.

Document every modification to the hardware or software. Choose components from reputable brands.

Train staff on proper shutdown procedures. These actions increase system stability. They also drastically reduce the chances of losing important programs or configurations.

Key Takeaways: PLC Loses Program – Reasons and Fixes

This article reviewed the most common reasons for program loss and presented practical solutions for each. Losing a stored program is a serious but manageable problem.

Most causes can be traced to power fluctuations, hardware faults, software errors, or environmental stress. With careful diagnosis and preventive strategies, such incidents can be avoided.

Stable power delivery, reliable components, updated firmware, and well-written code form the foundation of a resilient system.

A strong troubleshooting process ensures that problems are detected early before they cause major downtime.

Regular maintenance and backups protect vital data from accidental loss. Training personnel on safe shutdown procedures and correct system handling also improves reliability.

By combining technical precision with preventive care, users can greatly reduce the risk of losing their programs.

Ultimately, maintaining clean power, solid hardware, and disciplined software practices leads to safer, longer-lasting, and more dependable electronic systems.

FAQ: PLC Loses Program – Reasons and Fixes

What is program loss?

It’s when a stored program, configuration, or system state becomes corrupted, erased, or fails to run properly.

What causes program loss?

Power issues, faulty hardware, software bugs, memory corruption, bad configuration, firmware errors, or harsh environments.

How can power problems cause program loss?

Voltage dips, spikes, or sudden outages interrupt memory writes, leading to incomplete or corrupted data.

What hardware faults can lead to program loss?

Defective memory chips, bad bootloaders, damaged PCBs, or unstable reset circuits.

Can software bugs erase programs?

Not always. But logic errors or crashes can corrupt configuration files or stop execution.

What is memory corruption?

It’s when stored data changes unexpectedly due to interference, faulty addresses, or cosmic rays.

How can configuration errors cause problems?

Wrong I/O or boot settings may stop the program from starting, even if it’s still in memory.

Why is firmware important?

Old or buggy firmware can mishandle memory and power cycles, causing data loss.

What about external storage?

Corrupt or worn-out SD cards and drives can erase saved data or configuration files.

Do environmental conditions affect program stability?

Yes. Heat, humidity, or vibration can damage components and lead to failure.

How do I confirm if a program is really lost?

Read the device memory with a programmer and compare it to the original file.

How can program loss be prevented?

Use stable power, quality hardware, backups, good software logic, and routine maintenance.

Is program loss always permanent?

Not necessarily. Sometimes it’s a configuration or startup issue, and the data can be recovered.