A manometer is a simple yet essential scientific instrument used for measuring pressure. More precisely, it measures the difference between an unknown pressure and a known reference pressure.

The reference is often atmospheric pressure. It is a key tool in fluid mechanics and engineering. Its operation is based on the principles of fluid statics.

Typically, a liquid column, such as mercury or water, is used to indicate pressure levels.

This allows for a direct and accurate visual reading. This article explains what a manometer is. It also describes its working principles, types, components, and practical applications.

A Manometer

A manometer is an instrument that measures gauge or differential pressure. It operates by balancing a column of liquid against an unknown pressure. The height of the liquid column represents the pressure magnitude.

It is one of the oldest pressure-measuring devices. It contains no moving mechanical parts.

This makes it highly dependable. The liquid inside the instrument is known as the manometric fluid. This fluid must have specific characteristics suitable for accurate readings.

Principles of Operation

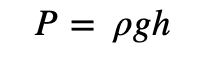

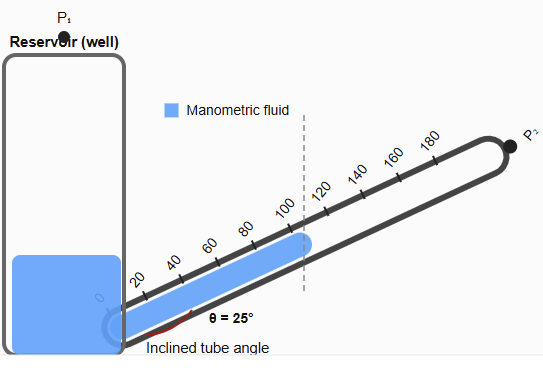

The manometer functions according to Pascal’s principle and the laws of fluid statics. In a continuous fluid, pressure remains the same at any given horizontal level. The fundamental equation governing its operation is:

Here P is pressure, 𝜌 is fluid density, 𝑔 is gravitational acceleration, and ℎ is the fluid column height. The difference in pressure is directly proportional to the difference in liquid levels.

The measurement is usually expressed in units such as millimeters of mercury (mmHg) or inches of water (inH₂O).

Key Components of a Manometer

A basic manometer consists of only a few components. It includes a glass or plastic tube that holds the manometric fluid. There is also a scale placed behind the tube for precise level readings.

The open ends or connection ports attach to pressure sources. The materials used must be compatible with both the manometric and process fluids.

Types of Manometers

Manometers come in several types. The choice depends on the pressure range and the specific application. The three main types are the U-tube, well-type (cistern), and inclined manometers.

U-Tube Manometer

The U-tube manometer is the simplest and most widely used form. It consists of a bent “U”-shaped tube. Both ends are either open or connected to pressure sources. When one side is exposed to the atmosphere, it measures gaugepressure.

The pressure is determined by the height difference between the two liquid columns. It also serves as a primary calibration standard.

The following figure represents a simple diagram of a U-shaped tube. It includes the manometric fluid, the scale, and the pressure connection points.

Left connection: unknown pressure; right connection: reference (often atmosphere). Then the difference in fluid heights is used to compute pressure via P=𝜌𝑔ℎ.

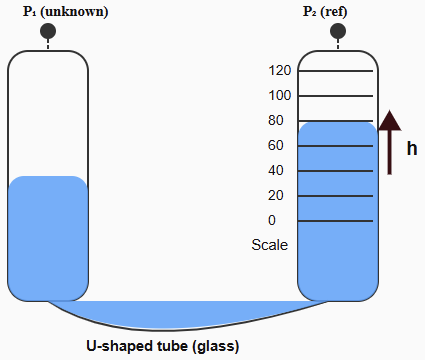

Well-Type Manometer (Cistern Manometer)

The well-type manometer features a large reservoir, or well, on one side. This replaces one arm of the U-tube.

Because the well has a large surface area, its fluid level changes only slightly. The pressure can be read from the single moving column.

The scale is adjusted to compensate for the small variation in the well. This provides a direct pressure reading.

The next figure illustrates a diagram of a well-type manometer showing the large reservoir and the single vertical tube with a scale.

Well (left), a large reservoir so level changes minimally. Right, a single vertical measuring tube with a scale displays the relative change in height used to compute pressure.

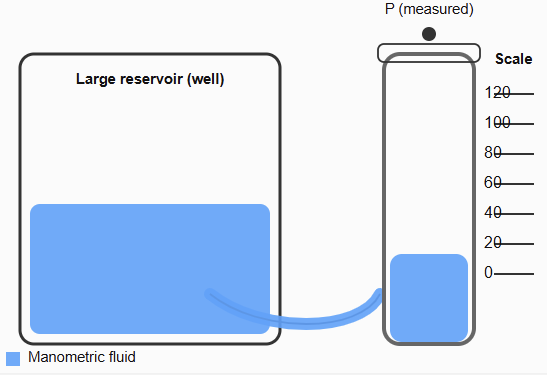

Inclined Manometer

In the inclined manometer, the measuring tube is set at an angle to the horizontal. This arrangement increases measurement sensitivity. A small vertical change in fluid level produces a larger movement along the inclined scale.

It is ideal for measuring very lowpressures. It is used for airflow, small pressure drops, or ventilation drafts.

The above figure indicates a diagram of an inclined manometer with the angle clearly labeled and the long, inclined scale shown.

Long inclined scale increases sensitivity. Left reservoir changes little; fluid moves along the incline for fine readings.

Other Manometer Types

Additional variations include the micromanometer for ultra-precise readings. There are also digital manometers.

These devices use electronic sensors but still follow traditional measurement principles. They provide digital displays and data logging capabilities.

Manometric Fluids

Selecting the correct fluid is essential. It must be stable, non-volatile, and immiscible with the process fluid. Common manometric fluids include:

- Water: Used for very low pressures. It is safe and inexpensive.

- Mercury: Suitable for high pressures because of its high density. It must be handled carefully due to toxicity.

- Oil: Used for special chemical compatibility or specific pressure ranges.

- Alcohol: Chosen for certain temperature ranges or low-pressure measurements.

Temperature affects fluid density. Corrections must be applied for accurate readings.

Measuring Different Pressures

Depending on its configuration, a manometer can measure gauge, absolute, or differential pressure.

- Gauge Pressure: One end of the manometer is open to the atmosphere. The other side measures system pressure relative to it.

- Absolute Pressure: One side of the U-tube is sealed and evacuated to create a vacuum. The other side connects to the process to measure pressure relative to zero absolute pressure.

- Differential Pressure: Both ends are connected to different pressure points. This measures the pressure difference, often used across filters or orifices.

Common Applications

Manometers serve many fields. Their uses range from simple air systems to industrial and scientific processes.

- HVAC Systems: Used to check duct static pressure. They also help balance airflow and monitor filter pressure drops.

- Medical Field: The traditional mercury sphygmomanometer measures blood pressure in mmHg. Mercury use is declining because of toxicity concerns.

- Weather Monitoring: Barometers, a type of manometer, measure atmospheric pressure. They assist in weather forecasting. High pressure indicates fair weather. Low pressure suggests storms.

- Industrial Processes: Used to monitor pressures in pipelines, tanks, and reactors. They also calibrate electronic pressure instruments.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages:

- Simple design and high reliability.

- No calibration required when used correctly.

- High accuracy and low cost for basic measurements.

Disadvantages:

- Bulky and not convenient for frequent readings.

- Fluid levels can be difficult to read precisely.

- Limited by fluid properties such as mercury toxicity or water freezing.

- Not suitable for direct integration with digital systems.

Manometer vs. Pressure Gauge

A manometer determines pressure using the height of a liquid column. A mechanical pressure gauge, such as a Bourdon tube, uses an elastic element.

This element flexes when pressure is applied. Electronic sensors rely on piezoresistive materials.

Manometers are more accurate at low pressures and for calibration. Gauges are better for high-pressure applications and automation. Both instruments remain important in industrial use.

Calibration and Accuracy

Manometers are considered primary standards for pressure calibration. Their accuracy depends on the correct fluid density and precise level readings.

The liquid’s meniscus must be read properly. Temperature compensation is essential for precision. Correct installation and handling also ensure accurate results.

Key Takeaways: What is a Manometer?

This article addressed the concept, operation, and applications of the manometer in detail. The manometer remains a cornerstone in the measurement of pressure. It combines simplicity with scientific accuracy.

Based on basic fluid mechanics principles, it shows how liquid columns can represent pressure differences clearly and visually.

Its various forms, such as the U-tube, well-type, and inclined manometer, serve different pressure ranges and sensitivities.

This makes it useful in laboratories, industry, and education. Despite the growth of digital sensors and electronic gauges, the manometer remains widely used. It continues to be a trusted calibration standard and an effective teaching tool.

Its precision, reliability, and straightforward design make it an enduring instrument in both science and engineering.

FAQ: What is a Manometer?

What does a manometer measure?

It measures the difference between an unknown pressure and a reference pressure, usually atmospheric.

How does a manometer work?

It balances a column of liquid against the applied pressure. The liquid height shows the pressure value.

What are the main types of manometers?

U-tube, well-type (cistern), and inclined manometers are the most common.

What fluids are used in manometers?

Water, mercury, oil, and alcohol. The choice depends on the pressure range and fluid compatibility.

What types of pressure can a manometer measure?

It can measure gauge, absolute, and differential pressure.

Where are manometers commonly used?

In HVAC systems, medical instruments, weather monitoring, and industrial pressure testing.

What are the advantages of a manometer?

It is simple, accurate, reliable, and inexpensive.

What are its disadvantages?

It can be bulky, hard to read, and limited by fluid properties.

How accurate is a manometer?

Very accurate when the fluid density, temperature, and meniscus are correctly accounted for.

Why is the manometer still used today?

Because it is easy to use, highly reliable, and ideal for calibration and educational purposes.