Safety is a top priority in industrial operations. Hazardous incidents can result in serious consequences.

These include loss of life, environmental harm, and financial losses. To manage such risks, engineers rely on the concept of functional safety.

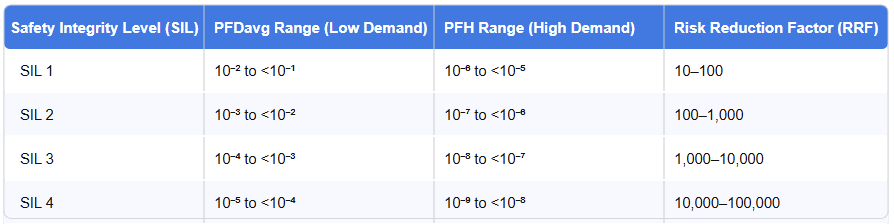

A crucial aspect of functional safety is the Safety Integrity Level (SIL). SIL provides a quantitative measure of the reliability and performance a safety function must achieve. It defines the level of risk reduction needed to reach an acceptable risk level.

Higher SIL levels correspond to a lower likelihood of safety function failure when required. This concept is established in international standards like IEC 61508 and IEC 61511. This article explores the four SIL levels and their practical significance.

What is Functional Safety?

Functional safety is a subset of overall safety. It ensures that systems and equipment respond correctly to their inputs. When a fault occurs, the system must enter a predictable and safe state. This state is known as fail-safe.

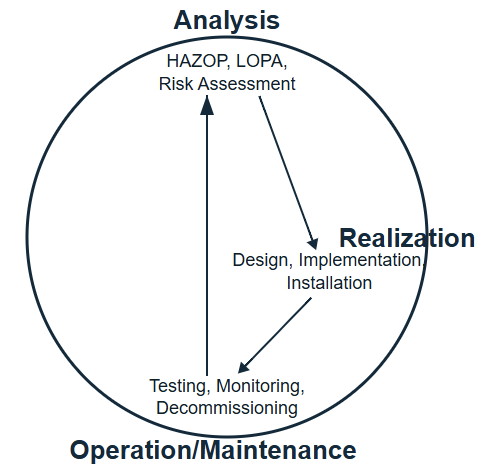

Achieving functional safety involves applying engineering principles throughout the system’s lifecycle. It covers every stage, from design to decommissioning. The objective is to reduce risks to a level that is “As Low As Reasonably Practicable” (ALARP).

The Role of International Standards

IEC 61508 is the primary standard for functional safety. It applies to electrical, electronic, and programmable electronic (E/E/PE) safety systems. Industry specific standards are derived from it.

For instance, IEC 61511 applies to process industries like chemical and petrochemical plants. These standards offer a structured framework for risk assessment and safety lifecycle management. They ensure a consistent and rigorous approach to safety engineering.

Defining Safety Integrity Levels (SIL)

A Safety Integrity Level (SIL) is a defined category ranging from one to four. It specifies the reliability required for a particular safety instrumented function (SIF). A SIF is a function designed to prevent or mitigate hazardous events.

SIL is not a property of the entire plant or individual components. Instead, components are classified as “SIL-capable” up to a given level.

Risk Reduction and PFD/PFH

SIL primarily measures risk reduction. Each higher SIL level represents an order of magnitude improvement in risk reduction. This improvement is quantified using probability metrics.

For low demand systems, the metric is the Probability of Failure on Demand (PFDavg). For high demand or continuously operating systems, the metric is the Probability of Dangerous Failure per Hour (PFH). A lower failure probability indicates a higher SIL.

The next figure indicates Table showing SIL levels, PFDavg, PFH, and Risk Reduction Factor (RRF) according to standard IEC 61508.

Determining the Required SIL

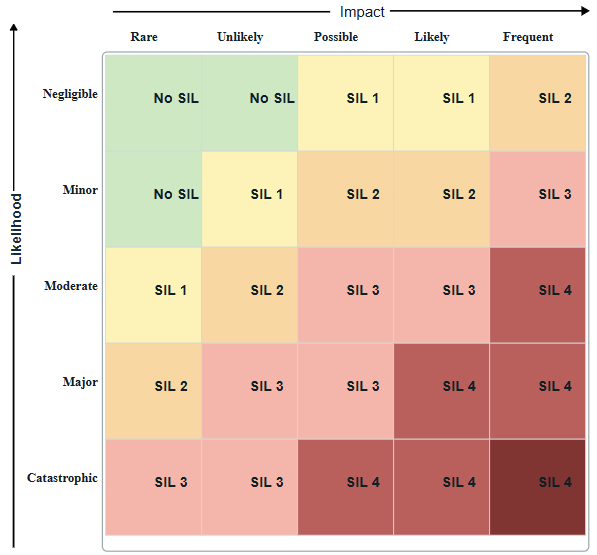

The required SIL for a SIF is determined through risk analysis. This process begins with a hazard and risk assessment (H&RA), such as a HAZOP study. It identifies potential hazards and their possible consequences.

The analysis considers both the severity of outcomes and the likelihood of occurrence. The following illustrates Risk matrix showing how consequence severity and occurrence frequency map to a target SIL.

The unmitigated risk is compared with the company’s defined tolerable risk level. The difference defines the required risk reduction. This value corresponds directly to a specific SIL target. Methods for SIL allocation include risk graphs, risk matrices, and Layers of Protection Analysis (LOPA).

The Three Requirements for Achieving a SIL

Three criteria must be met to achieve a SIL. These are hardware safety integrity, systematic safety integrity, and architectural constraints. Hardware integrity addresses random failures and is quantified through PFD or PFH.

Systematic integrity focuses on preventing design or human errors across the safety lifecycle. Architectural constraints include hardware fault tolerance (HFT) and safe failure fraction (SFF). The overall SIL is the lowest level satisfied by all three criteria.

SIL 1: The Lowest Level of Integrity

SIL 1 is the entry level safety integrity. It provides a moderate risk reduction factor between 10 and 100. It suits low risk applications with minor potential consequences. Examples include basic process alarms or non-critical controls. SIL 1 systems require simple diagnostics and basic failure detection methods.

SIL 2: Moderate Safety Requirements

SIL 2 demands higher performance. It offers a risk reduction factor between 100 and 1,000. This level is used in intermediate risk industrial applications. Failures could cause serious injuries or operational disruptions.

Common examples include chemical and power plants. SIL 2 systems require stricter designs. They may include redundancy and more rigorous testing.

SIL 3: High-Integrity Systems

SIL 3 provides significant risk reduction. The reduction factor ranges from 1,000 to 10,000. It applies to high risk scenarios with potentially catastrophic consequences. Examples include emergency shutdowns in oil and gas or nuclear power systems.

Achieving SIL 3 involves dual channel architectures and advanced diagnostics. It also requires extensive verification processes. These systems are more costly and complex to build.

SIL 4: The Highest Level of Safety

SIL 4 is the maximum integrity level. It offers risk reduction between 10,000 and 100,000. It applies to extremely hazardous environments with catastrophic potential. Examples include aerospace, defense, or nuclear systems.

SIL 4 often requires triple redundancy and fail operational capability. It is rare in general industry because of its high complexity and cost.

The Safety Instrumented System (SIS)

Safety functions are implemented through a Safety Instrumented System (SIS). It operates independently from the basic process control system (BPCS).

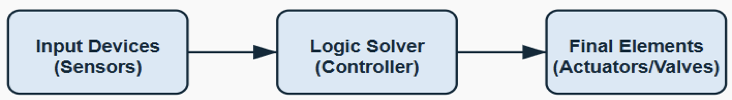

A single SIS can manage multiple SIFs with varying SIL requirements. The SIF defines the function. The SIS is the physical system that executes it. The figure below specifies a block diagram of an SIF showing Input Devices (sensors), Logic Solver (controller), and Final Elements (actuators/valves).

Components of a SIF

A SIF typically includes three components. These are an input device, a logic solver, and a final element. The input device (e.g., sensor) measures a process variable. The logic solver (e.g., safety PLC) processes the signal and decides on an action.

The final element (e.g., valve or actuator) brings the process to a safe state. Each component must be SIL-capable to meet the overall requirement.

Architectural Constraints and Hardware Fault Tolerance

Achieving a SIL requires meeting architectural constraints. One key factor is Hardware Fault Tolerance (HFT). HFT is the system’s ability to function safely despite faults.

For example, an HFT 1 system tolerates one fault while maintaining safety. Higher SIL levels often require higher HFT. This usually means more redundancy in the design.

Systematic Safety Integrity

Systematic integrity addresses non-random failures. These include design flaws, software bugs, or human mistakes. It is managed through strict adherence to lifecycle processes. This includes documentation, design standards, testing, training, and audits. Proper management of these activities ensures consistent safety performance.

The Safety Lifecycle

SIL implementation covers the full safety lifecycle. It begins with hazard identification and risk assessment. This is followed by defining safety requirements and target SILs for each function.

Then come the design, implementation, installation, and validation stages. Operation, maintenance, testing, and decommissioning are also essential. This structured approach ensures consistent safety management over time.

The figure above stipulates a circular diagram showing safety lifecycle stages: Analysis, Realization, and Operation/Maintenance.

Testing and Validation

Testing and validation confirm that a system meets its target SIL. Validation ensures the design can achieve the required SIL. Verification confirms that implementation matches the design. Regular proof testing during operation maintains reliability. Higher SILs require more frequent and detailed testing.

Misunderstandings about SIL

SIL applies only to specific safety functions. It does not apply to entire facilities or to individual mechanical devices. For example, it is incorrect to label a component as “SIL 3.” The safety function, not the component, requires SIL 3. Also, a higher SIL is not automatically better. It must be suitable for the specific identified risk.

Industry Applications

SIL is used across many industries. In oil and gas, SIL systems manage emergency shutdowns. Railways use SIL 4 for critical signaling systems. Food processing plants may use SIL 2 for moderate hazards. The selected SIL always matches the level of potential risk.

Key Takeaways: What are Safety Integrity Levels?

This article reviewed Safety Integrity Levels as a key principle in functional safety engineering. They provide a measurable standard for reliability and risk reduction of safety instrumented functions.

Defined by standards such as IEC 61508, the four SIL levels (1–4) guide the design, implementation, and maintenance of safety critical systems. Applying SIL helps companies manage risks effectively.

It ensures that both human life and the environment are protected from dangerous failures. Through proper SIL assessment, engineers can decide what level of protection is truly necessary. This avoids both under design and over design. It also saves costs while maintaining safety.

SIL implementation supports compliance with international safety regulations. It promotes continuous improvement in industrial operations.

By ensuring that every safety function meets its intended performance, SIL helps maintain system reliability.

It also contributes to making systems more efficient and resilient. Ultimately, it strengthens trust in automated safety systems across all industries.

FAQ: What are Safety Integrity Levels?

What is a Safety Integrity Level (SIL)?

SIL is a measure of how reliable a safety function must be to reduce risk to an acceptable level.

How many SIL levels are there?

There are four levels: SIL 1 (lowest) to SIL 4 (highest). Higher levels mean greater risk reduction.

How is SIL determined?

Through risk analysis methods such as HAZOP or LOPA, comparing unmitigated and tolerable risks.

What does SIL measure?

It measures the probability that a safety function will fail when needed.

Does SIL apply to the whole plant?

No. It applies to a specific safety instrumented function (SIF), not an entire facility.

What are key requirements to achieve SIL?

Hardware integrity, systematic integrity, and architectural constraints.

Are higher SIL levels always better?

No. The required SIL should match the actual risk — higher isn’t always necessary.

Where is SIL used?

Common in oil & gas, chemical, power generation, and other high-risk industries.